On Friday, 27 May 1904, the Sri Kumala, a merchant ship sailing under the Dutch flag, ran aground on the reef off Sanur Beach in Bali. The vessel carried paying passengers and had a cargo manifest comprising bread, sugar, fuel oil, “Chinese kepeng coins,” and some ceramic wares.

The ship was owned by Kwee Tek Tjiang, a shipping operator from Surabaya of Chinese descent, who enjoyed the benefits of the Dutch stratified legal system that relegated natives to the lowest echelon of justice available under the law, with Chinese and mixed-race individuals enjoying more favorable terms, with Europeans ruling the legal roost subject exclusively to the standards of Dutch law.

The grounding of the merchant ship would warrant little mention in the Island’s history, except that the incident and its immediate aftermath punctuated a bitter period in colonial history culminating in a Dutch military intervention into nearby Badung (Denpasar) and the battle-to-the-death (ritual suicide/”puputan“) that caused an estimated 1,000 deaths on 12 September 1906.

The early years of the 20th century were marked by furtive efforts by the Dutch Colonial Government to exert control over the Island’s recalcitrant population, who had historically proven themselves essentially ungovernable.

Mesatia

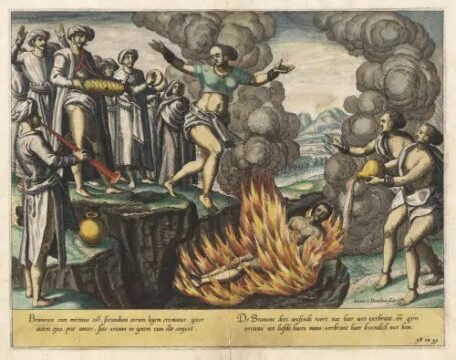

The most famous of these traditions relates to women: the sacrifice of the widows of a Balinese Raja or King. “Mesatia” (from satia, faithful) resembles the Indian ritual of settee.

Among the last documented “mestatia” in Bali took place two years before the Dutch Colonial intervention in Sanur. Despite ong-standing formal commitments by the Dutch that they would not interfere in the cultural life and traditions of the Balinese, Colonial administrators in Batavia (Jakarta) and Surabaya took umbrage at plans in the Tabanan region of Bali for several wives of the late Raja to cast their bodies onto their deceased husband’s funeral pyre. The Dutch rulers saw the ritual of self-immolation as “barbaric” and tried unsuccessfully to halt the sacrifice.

Dubois, a Belgian writer in the early 19th century, described the self-sacrifice of “mesatia” as follows: “She again performs the ritual gestures… her father lends her his kris, with which she wounds her arms and shoulders. She draws blood from the tip of the kris from the wounds she has inflicted and uses the blood to redden her foreheads.. She indicates in this way… that she has no fear of death.. She joins her voice to the pious chants that she hears around her… She arrives at the deadly end of a plank (suspended over the funeral pyre)…returns the kris to her father, and, crossing her hands on her breast, jumps to the right, is seen for a moment in the air, and is engulfed in the glowing ember… A dozen men, armed with bundles of firewood and long bamboo impregnated with oil, throw them and pile them on top of her.”

Dubois’ depiction continued, describing the demise of another death-seeking widow: “She leaves her relatives… from her father, she receives the kris with which she stabs herself downward from above her left shoulder; then she collapses and her father with her brothers lift her to throw her, quivering body, into the fire. No sign of fear or repugnance is visible at all on people’s faces.”

Much to the chagrin of Dutch officials, the “mestatia” ritual in Tabanan was held, prompting the reigning Dutch officials to subsequently seek to settle a score and try to bring the Balinese people to heel.

Back to the 1906 Grounding of the Sri Kumala

Using his birthright of an elevated legal status, the ship’s owner, Kwee Tek Tjiang, filed what is widely believed to have been a false report with the Colonial Resident, alleging that a large sum of Ringgits and a quantity of Chinese Kepeng Coins had been stolen from the grounded ship. Despite the Balinese swearing an oath that they were blameless in any theft, the Dutch ruled nonetheless that an apology was due and the Badung principality must pay compensation to the Chinese merchant before an official deadline of January 9, 1905.

The deadline came and passed, providing a raison d’être for the landing of a Dutch colonial invasionary force on 19 September and the ensuing bloodbath of the Badung “Puputan” that on 20 September 1906, in which the King, his Royal Court, and followers, fearing imminent forced exile from Bali, chose to die in a fusillade of bullets or rushed self-impalement on the drawn bayonets of the Dutch soldiers.

Expecting the Balinese to submit to their superior firepower, the Dutch were said to have been dumbfounded and overwhelmed by the Balinese response and the resulting overwhelming carnage.

The Dutch attempt to create a show of military force to curb what they perceived as Balinese barbarism, ironically, left them guilty of committing a historically barbaric act and a never-to-be-forgotten crime against the Balinese people and their culture.