Editorial: A Step to Refloat the Indonesian Tourism Economy

“When one door closes, another opens; but we often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door that we do not see the one which has opened for us.”

Alexander Graham Bell – Inventor of the Telephone

This quote came to mind when considering the industry-wide chaos being experienced by the International Cruise Industry at the moment and what, if any, opportunities exist to rebuild the Indonesian economy amidst this current disarray.

This editorial, calling upon nearly two decade’s experience in cruise industry management, suggests that a unique strategic opportunity exists for Indonesia to become a leading international cruise hub.

Indonesia as an International Cruise Hub

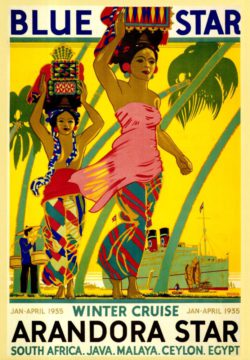

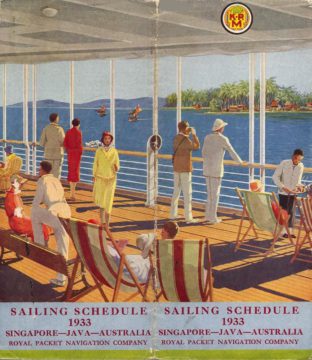

In our view, Indonesia is a near-perfect cruise destination. Covering a 5,150-kilometer stretch bridging the distance between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Indonesia’s geographical breadth is roughly equal to the distance between Seatle and the Bermuda Islands. With 17,508 islands, of which around 60% are inhabited, Indonesia has ports-of-call and cruise destinations galore.

In fact, it’s worth noting that no single individual has ever managed to spend a single day on every Indonesian island. Such an Odyssean quest would require 48 years to accomplish even without calculating traveling time between islands.

Unparalleled Choice of Cruise Stops

The Indonesian national motto of “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” or “Unity in Diversity” suggests the wide variety of exciting cruise stops available to cruise ships that would take the time to linger and explore the archipelago. The Republic’s islands are home to ancient and sophisticated cultures – societies that built the 9th century Borobudur Temple and the megalithic Gunung Padang site in West Java dated as far back as 20,000 BCE.

Complex and esteemed cultures already existed in Indonesia in the periods well before even semi-domesticated animals grazed the medieval fields outside Notre Dame in Paris. With at least 350 ethnic groups speaking some 483 languages and dialects, Indonesia guarantees that a new and enchanting destination is never more than a short sail away for any ship cruising its waters.

Indonesia – the Emerald Equator

Because Indonesia is an equatorial nation, it offers arguably the world’s best climate for cruising. Located primarily in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCV) – an area sailors call “the doldrums” – Indonesia experiences “calm weather” throughout the entire calendar year. There are two seasons to the year: the “dry” that falls between May and October, and the “wet” between November and April. While rainfall is plentiful in some parts of Indonesia during the “wet,” – it’s rare for it ever to rain for days-on-end, still allowing daily shore programs from ships to continue as planned.

Further good news to cruise passengers and ships’ crews alike: Typhoons and large scale storms tend to skirt far to the north and south of Indonesia’s main geographical confines. While strong, swift currents are found in the north-south straits that punctuate the archipelagic chain, these pose no obstacle to modern cruise ships.

Indonesia also offers a growing network of modern airports facilitating the embarkation and disembarkation of passengers on extended cruise itineraries traveling the Nation’s entire length and breadth.

How Big is the Cruise Market?

According to the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), some 30 million passengers took a cruise in 2019, representing some US$134 billion in sales. A labor-intensive sector of the economy, more than 1.1 million people work in the cruise industry, sharing a total payroll estimated at US$45.6 billion.

Where are the major Cruise Areas?

Historically, the world’s leading cruise areas are situated in the Caribbean and Meditteranean, fed primarily by North American and European passengers. In 2019, 76.8% of all cruises operated in the following areas: Caribbean (34.4%), Meditteranean (17.3%), Europe non-Meditteranean (11.1%), China (4.9%), Australia/New Zealand/Pacific (4.8%), and Asia (4.3%)

The Situation of the Global Cruise Industry

When the global pandemic suddenly descended in the early months of 2020, the approximate 272 ships operating worldwide were especially hard-hit. Ships were quickly identified as threatening “clusters of infection” as confirmed cases of COVID-19 were widespread among ships’ passengers, many of whom were elderly – a group known to be at most significant risk of dying from the disease.

As the world struggled to come to terms with the novel coronavirus, many ships became five-star refugee ships – suddenly refused landings rights at ports worldwide. These ships were forced to become like the mythical ancient “Flying Dutchman” of yore, doomed to sail the oceans for a seeming eternity. Unable to make shore, passengers and crews were often confined to their quarters for weeks, and in some cases, months, waiting for the opportunity to disembark and rejoin to their families.

Now more than six months after the pandemic’s advent, almost the entire global cruise cruise fleet, once valued at US$167 billion, but devalued by US$4 billion since the crisis began, sit idle and at anchor tended by skeletal crews. While cruise lines hemorrhage cash at an unprecedented rate, the industry’s expert strategizes on how they will manage to relaunch their parked ships, regain passengers’ confidence, and formulate itineraries to ports that most recently shunned the visit of ships they saw as contagious.

An Opportunity for Indonesia?

We believe that the current upheaval affecting the global cruise industry holds a unique opportunity for Indonesia to seek to become an international cruise center and create a significant force for the Nation’s economic development.

In the belief that President Joko Widodo’s recent calls for inter-sectoral cooperation to resolve the current economic crisis are genuine, we suggest that Indonesia now needs to take the next step. What’s needed is for the President and Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, to establish a Coordinating Agency for Cruise Shipping. Such an Agency would be tasked to take the existing natural charms of Indonesian cruising and create an equally attractive regulatory environment for international cruise shipping. Providing necessary changes in the status quo were put in place, there is little doubt that the major cruise line operators would quickly set up and take notice of Indonesia as a location for a viable cruise hub.

The Elephant in the Room

Recommendations in this editorial are certain to be greeted with a chorus shouting: “But what about the virus?”

As we presented earlier in our Editorial “COVID- Damned if we Do and Damned if We Don’t” , the coronavirus is likely to be with us for a considerable time to come. If Indonesia waits for a final cure before it does all that it can to save the National Economy, the resulting devastation may prove irredeemable with little left economically to save.

Instead, why not formulate the most stringent protocols covering cleanliness, health, and safety for cruise ship operations in Indonesian waters? Then, advise cruise lines wishing to join an Indonesian cruise hub that these are the rules that will strictly apply for the safety of crews, passengers, and the communities visited ashore. If deemed necessary by the Indonesian health authorities, qualified medical personnel could even be assigned to travel on every ship where continuous testing and screening could occur. Given the current state of international cruising and the desperate search under way by cruise line looking for workable itineraries, the cruise operators would hardly expect anything less. Moreover, we think cruise operators might eagerly and urgently embrace an attractive cruise destination presenting viable rules that would allow them to now begin the urgent formulation of new cruise itineraries.

Creating an Attractive Regulatory Environment for Cruise Ships

Anticipating the areas that would need to be addressed to create a regulatory environment amiable to creating an Indonesian Cruise hub, here’s a shortlist of some of required changes and improvements:

- Implementation of recently promised changes in import taxes promised by Minister Luhut (See: Tax on cruise ships & Yachts Set to Go? ).

- Unlimited cruise permits for passenger ships operating in Indonesia.

- Competitive tax treaties to allow cruise ships to operate in Indonesia waters much in the way they operate elsewhere.

- Attractive financial incentives to encourage, but not necessarily compelling, the adoption of an Indonesian flag for cruise ships operating in Indonesian waters. This is needed to make reflagging a modern cruise ship under the Indonesian flag an attractive proposition both financially and legally.

- Deregulation of manpower rules to permit foreign crew members largely unencumbered employment on ships deployed in Indonesian waters with incentives offered to encourage Indonesian nationals’ hiring.

- Allowing the use of duty-free goods on the Indonesian cruises and the trans-shipment of these items under seal from airports to vessels in Indonesia.

- The transparent and clear codification of maritime rules and regulations to minimize any potential abuse in the issuance of sailing permits and port clearance procedures.

While some of these changes require significant changes in how Indonesia currently views ship operations, the resulting creation of an Indonesian international cruise hub we believe warrants the effort. The many benefits that would accrue to the Nation are:

- substantial foreign exchange earnings,

- much-needed tourism revenues flowing to remote and economically deprived areas of Indonesia, and

- many well-paying employment positions that the Indonesian cruise hub would create.

Another benefit all too often overlooked from creating a modern maritime fleet in Indonesia is the resulting natural enhancements to national defense. Over time, a growing fleet of modern Indonesian vessels using the latest equipment and technology operated as required under International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules, with well-qualified Indonesian mariners working in the wheelhouse and engine rooms, will prove to safeguard the Republic of Indonesia. These vessels would be at the Nation’s disposal to assist in times of natural disaster or, if needed, to defend Indonesian sovereign territory.

And, for anyone thinking the last point a stretch, let’s not forget that Indonesia is, after all, a nation of islands. What’s more, in 1982, during the Falkland War, if the United Kingdom was unable to commandeer the services of the MS Queen Elizabeth and the MS Canberra as troop transports, the final result of that conflict might have been markedly different.

Related Link